Scientists from the Leiden University Medical Center discover how NOT to get type 1 diabetes

&width=710&height=710)

Type 1 diabetes

More than 12 million people in the world suffer from type 1 diabetes (T1D). This disease is caused by the body's own immune system destroying the cells that make insulin (beta cells) in the pancreas. As a result, T1D patients make little or no insulin. Insulin is a hormone that allows sugar in the blood to be absorbed by the body and to be used as energy in muscles and organs. Insulin keeps the amount of sugar in the blood in balance. In fact, too much (hyper) or too little (hypo) blood sugar can be harmful.

Currently, there is no cure for T1D. Patients must administer insulin with an insulin pen or insulin pump for life. Despite insulin treatment, TD1 patients are at risk for eye problems, damaged kidneys, and cardiovascular disease as a result of T1D; in other words, insulin therapy is not a cure.

Stress as culprit

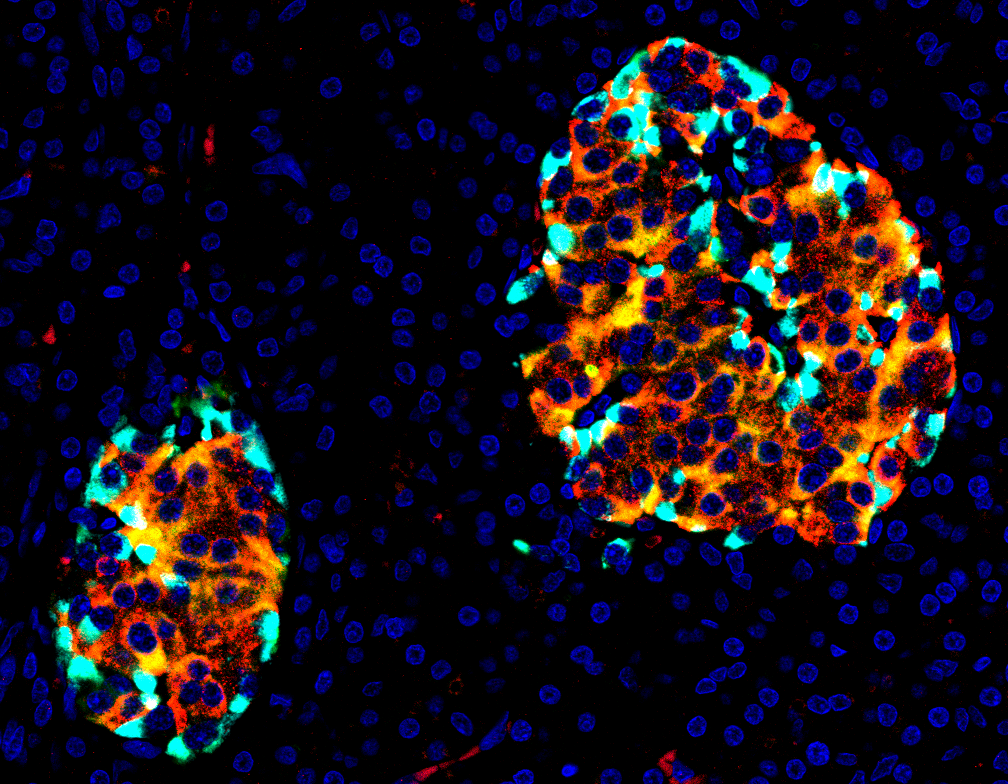

Why some people develop T1D, and others do not, remains unclear. For a long time, it was thought that the disease arises from a mistake in the immune system, causing the body to destroy its own beta cells. In recent years, this understanding has changed, thanks in part to Roep's research. As a result, we now know that it is not the immune system itself that derails, but that stressed beta cells send signals, causing the immune system to see them as “wrong".

Roep: “Beta cells are very hard workers. Each beta cell can make as many as one million insulin particles (molecules) per minute. This allows sugar to be quickly absorbed from the blood after a meal. But this process can also cause beta cells a lot of stress. If the beta cell can no longer manage that stress, the cell unknowingly signals the immune system to destroy it. We have now discovered why beta cells can cope with this stress in some people but not quite as well in others.”

A valve to blow off steam

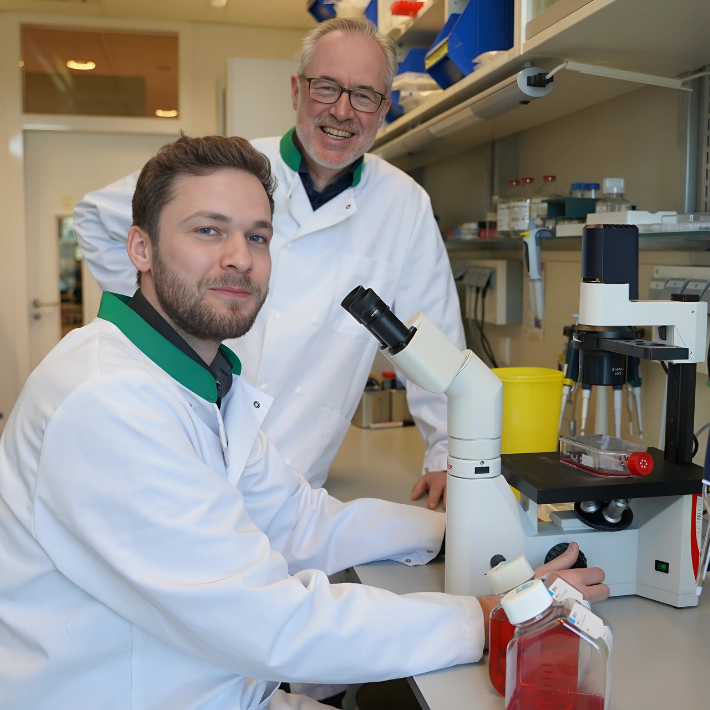

“One small variation in the DNA of the insulin gene produces a protective effect against T1D,” says Dr. René van Tienhoven, researcher and a T1D patient himself. Tienhoven: “The beta cells in people with the protective variant are equipped with a kind of valve. The valve allows the beta cells to blow off steam during high stress and therefore remain invisible to the immune system. Thanks to this valve, the beta cells are also fitter and work better. They are a kind of super-beta cells,” he says.

'Islets on fire': stressed beta cells (yellow/orange). Picture by René van Tienhoven and Bart Roep.

A better prognosis

One in five patients with T1D has the protective genetic variant (and thus beta cells with the valve) and yet they still developed diabetes. This implies that the valve does not offer complete protection. However, according to the new study, the disease progression of these patients is milder. “Provided they inject enough insulin, these T1D patients often retain beta cells of their own. As a result, they make a little insulin themselves and can regulate their blood sugar better. Their prognosis is therefore better: the disease rarely leads to complications in this group,” says Van Tienhoven.

Personalized treatment

Thanks to the LUMC researchers, we now know that the disease progression in T1D patients can differ and that this is partially caused by a tiny, natural variation in the DNA of the insulin gene. Insulin therapy targets the symptoms, not the cause of T1D. Various interventional therapies have been tested in an attempt to cure T1D, but so far they have been temporarily effective in some patients at best. Research is now underway to determine whether the genetic variant can explain why certain intervention therapies have an effect or not, and in which patients. This knowledge will allow a treatment to be better tailored to the individual patient. Testing patients for the genetic variant thus not only provide valuable information about the severity and prognosis of the disease progression but also about the possibilities for personalized treatment of T1D.

This discovery potentially offers other future applications that may hold great promise for T1D patients. For example, LUMC is currently performing islet transplantations in patients with severe T1D. In this complex procedure, the so-called Islets of Langerhans in which the beta cells are located, are isolated from a donor pancreas. In the Netherlands, this procedure is performed only at the LUMC. Furthermore, stem cells are grown into beta cells at the LUMC. Roep: “We can screen pancreatic or stem cell donors for the protective variant to improve the outcome of islet transplantation and stem cell therapy. In the future we may even be capable of making a small genetic modification to introduce the valve in cultured beta cells. These methods are not yet developed to the point where we can use them to treat T1D patients, but it holds great promise for the future.”

More information

The research results are published in Cell.

&width=710&height=710)

&width=710&height=710)